Cover via AmazonAs Slang Changes More Rapidly, Expert Has to Watch His Language

Cover via AmazonAs Slang Changes More Rapidly, Expert Has to Watch His LanguageWeb Makes Keeping Up With Argot Tough; Mr. Dalzell Is a Real 'Big Noise,' Though

BERKELEY, Calif.—Tom Dalzell was thrilled last month when he came across a weird new verb: "rickroll."

Then he went online and saw that "rickrolling"—the Internet prank that involves sending someone a link to the music video for Rick Astley's "Never Gonna Give You Up"—has been around for four years. That's an eon in the world of slang, enough time to render a term stale.

For most people, being late to a language trend isn't a problem. But Mr. Dalzell, a 59-year-old union leader by day and slang expert after hours, is now in the process of updating the New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. And as informal language evolves faster than ever, Mr. Dalzell is finding it trickier to keep up. (click below to read more)

"Yesterday's cutting-edge is today's ho-hum," he says.

The problem: Slang is born when groups outside the mainstream invent their own language—verbal code that can quickly lose its punch once others catch on. That process used to take a while. But now that social media sites like Facebook and Twitter let people post messages for anyone to see, slang gets exposed much more quickly.

"It's really shortened the shelf life," says Mr. Dalzell, who is considered to be a real "big noise," or a very important person, among word whizzes like Jesse Sheidlower, editor-at-large at the Oxford English Dictionary.

Mr. Dalzell isn't only dealing with a faster velocity of slang creation. He also contends with fake slang, wherein people invent words and post them online. Anyone, for instance, can edit the Web-based Urban Dictionary. "It's like naming a star after yourself," sniffs Mr. Dalzell.

Urban Dictionary CEO Aaron Peckham says "Oh, man, I love reading quotes like that." The site, he says, provides "a lot of provably false information. It's supposed to be entertaining."

Keeping volumes current with slang "is a really big challenge," says Andrea Hartill, who edits Mr. Dalzell at the New Partridge dictionary. So to keep up, Mr. Dalzell resorts to some creative methods. Last month, he hung out at an online forum for blow-up doll enthusiasts long enough to discover "iDollator," a person with a fetish for dolls.

To learn about the verb "to bling out"—or, to decorate with excessive ornamentation—he studied a forum for acolytes of the singer Taylor Swift.

There, one fan wrote about Ms. Swift's jewel-studded guitar, "It would be cool to bling out my guitar, but I can't even imagine how long it took them to stick all those rhinestones on there."

Other recent revelations: "rando," a stranger or random person and "bone out," to leave.

Mr. Dalzell became a slang expert by accident. In his twenties, he studied law at the United Farm Workers union through an old-school apprenticeship under union lawyer Jerry Cohen. Mr. Dalzell was captivated by his boss's quirky charisma and decided to write a roman à clef based on their work together.

But he wanted his book's alter ego, Gabby, to one-up the character inspired by Mr. Cohen, named Lance. So he started collecting books on slang to make Gabby sound snappier.

Soon, Gabby's dialogue was sprinkled with Hawaiian surfer lingo, Yiddish-isms and other arcane slang.

In one scene, Gabby asks, "How do you feel, Lance?" Lance says, "Too pooped to pop. And you?" Gabby answers, "Rode hard and put away wet." (Translation: "How do you feel, Lance?" "Too tired to even have sex. And you?" "As exhausted as a sweaty horse.")

The novel was never finished, but Mr. Dalzell's slang obsession grew. He amassed a giant library of slang books, then started writing his own. By the 1990s, his hobby had established him as one of the world's top slang experts. "I see him as probably the greatest person in slang right now in America," says Paul Dickson, a writer whose credits include "Drunk: The Definitive Drinker's Dictionary."

When daredevil Evel Knievel and his wife sued ESPN in 2001 over a photo caption that called him a "pimp," the network hired Mr. Dalzell as an expert witness. In a report for the case, Mr. Dalzell said young Americans define a pimp as "an alluring, charming ladies' man," not "a procurer of prostitutes." Mr. Knievel lost.

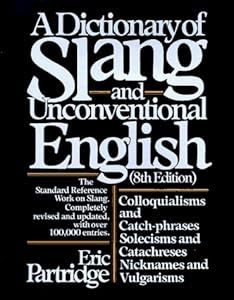

By then, Mr. Dalzell had been contacted by Routledge, the publishing house whose dictionary of slang and offbeat language, first printed in 1937 and authored by lexicographer Eric Partridge, needed an update. Routledge chose Mr. Dalzell and his friend Terry Victor for the task, and they published a new version in 2005.

Six years later, that dictionary is already out-of-date. In it, Mr. Dalzell included the noun "bling," a vulgar or ludicrously ostentatious display of wealth, but omitted newer offshoots, like "to bling out."

As for rickrolling, Mr. Dalzell was embarrassed when he realized he had actually encountered the term before—at a 2008 talk he'd given at Google Inc. There, an attendee called out, "Hi, do you think that short-lived Internet fads deserve to be recognized as slang? I'm thinking of things like LOLcat or rickroll or something like that."

Mr. Dalzell had to concede he had never heard those terms and made a mental note to look them up. When he came across rickrolling again last month, he thought he was seeing it for the first time. Only later did he remember the earlier encounter.

No comments:

Post a Comment