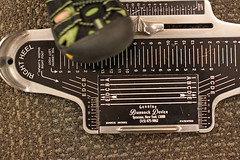

Image by theloushe via FlickrMaker of Foot Measurer Tries to Stop Other Shoe From Dropping—On It

Image by theloushe via FlickrMaker of Foot Measurer Tries to Stop Other Shoe From Dropping—On ItIconic Brannock Device Hangs On By Its Toes Against Foreign-Made Rivals

LIVERPOOL, N.Y.—Many have tried, but no one has ever come up with a more elegantly simple way to measure the human foot than Charles Brannock, inventor of that ubiquitous metal gadget found in shoe stores and known, fittingly, as the Brannock device. (more after the break)

Created in the 1920s, Mr. Brannock's tool is among the most enduring industrial designs ever. The company's original paperwork now resides in the Smithsonian Institution. Cameron Kippen, a foot historian and podiatrist in Australia, calls them an "icon of quality" that changed the way shoes were fitted.

Allen Edmonds Shoe Corp.'s chief executive, Paul Grangaard, keeps one in his office. He used it most recently to measure the foot of Osmo Vanska, the Finnish music director of the Minnesota Orchestra, to whom he was giving a pair of shoes.

There's even an alternative-rock band in Kansas City called "The Brannock Device," a name picked, according to one of the band's founders, guitarist Jeremy Schutte, because the drummer once worked in a shoe store. "We loved the name," he says. "There's a little nostalgia to it—going to the shoe store and getting your shoe fitted."

But defending the Brannock legacy from competitors, who produce cheaply overseas, has become an uphill battle. Sal Leonardi bought the Brannock Device Co. Inc. from Mr. Brannock's estate in 1993 after the inventor died at age 89, and he promised to keep the factory in the Syracuse area for at least five years. That was an easy pledge for Mr. Leonardi, a passionate advocate of American manufacturing. He says he bought Brannock in part because he figured its then domination of a microscopic industry would assure its success.

Its 1929 patent, however, expired long ago. Over the last two decades, the Brannock device has become a target for copycats. Although Mr. Leonardi won't give details on sales at the closely held company, he says foreign-made devices have cut into his market.

There isn't much the company can do to stop imitators. Mr. Leonardi's attempt to trademark the product's distinctive shape was rejected. "We don't mind competing with someone making a foot-measuring device, but not if they can make them to look exactly like ours," says Mr. Leonardi. Which they can.

Nobody else can call it a Brannock device, since the name is protected by copyright. Beyond that, just about anything goes. And does.

In his office the company's tiny 10-employee factory outside Syracuse, Mr. Leonardi keeps a handful of copies. One knockoff even includes a copy of Brannock's original instruction sheet—with only the name of the company changed.

The fuzzy photos on the knockoff's instruction sheet are of Mr. Brannock's own hands holding the device, and of the inventor using it to measure a woman's foot. The copycat device is such a faithful imitation that it doesn't include modifications made to Brannocks by Mr. Leonardi over the past decade, such as slightly streamlining the knob used to mark the ball of the foot.

Marvin Bearak, whose company makes that particular copy in China, says it's possible they copied the instructions early on, but they have since updated the instruction sheet. "We basically knocked it off, reverse-engineered it," says Mr. Bearak, president of Chicago-based Justin Blair & Co., a maker and distributor of shoe-store equipment.

The driving force is price, he says. An authentic Brannock made in the U.S. sells for about $60, while Chinese-made versions sell for less than half that. Mr. Bearak's product is called a "Ralyn foot measuring device," but held alongside the real thing, it's difficult to see much difference.

Brannock has a complex relationship with its imitators. Mr. Bearak's company, besides selling the Chinese-made knockoffs, distributes authentic Brannock devices purchased from Mr. Leonardi. Some customers insist on the real thing, says Mr. Bearak. Others want to save money.

David Murphy, president of Red Wing Shoe Co. in Red Wing, Minn., is among the purists. He says the firm specifies authentic Brannocks when it opens new stores, and he doesn't mind paying over twice as much for them, "because they last forever."

"A Brannock device is very, very important to us," he says. "We train our people on them."

Mr. Brannock was the son of a Syracuse shoe merchant who began developing his device while still a student at Syracuse University. At the time, the main tool available was the "Ritz stick," a simple wooden ruler that gauged only foot length, not the other dimensions measured by a Brannock. Mr. Brannock made his prototype out of erector-set pieces and applied for a patent in 1927.

They were an instant hit, though business really took off during World War II, when the government contracted Brannock to produce a version of the device that allowed soldiers to have both feet measured at once. That sped the process of distributing footwear.

Jonathan Walford, a shoe historian, says there is a "whole Brannock field out there—guys who collect and are really into them."

Berry Craig estimates he has about 75 vintage Brannocks on specially built shelves in a closet at his home in Kentucky. "If they're good enough for the Smithsonian to collect," says the history professor at West Kentucky Community & Technical College, "they're good enough for me."

Beyond low-cost copycats, the biggest challenge facing Brannock today is that many people buy shoes on the Internet or in self-service stores where getting fitted by an expert isn't an option. New technologies also have emerged to measure feet electronically, but those systems are far more costly.

Back at the Brannock factory, Mr. Leonardi says substituting cheaper materials isn't an option. Mr. Brannock insisted his devices be made to be as durable as possible, so Mr. Leonardi has resisted advice to reduce prices by using plastic or other materials. "That's something Mr. Brannock would never accept," he says, "and neither would we."

No comments:

Post a Comment