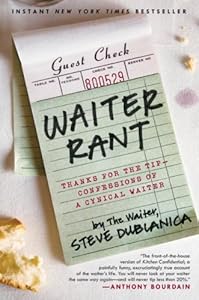

Cover via Amazon

Cover via AmazonService Not Included

Book title:Keep the Change: A Clueless Tipper's Quest to Become the Guru of the Gratuity

For years Steve Dublanica lived off tips. The author of the blog (and, later, the book) "Waiter Rant" recalls spending almost as much time fretting over tips as serving customers. Relying for his livelihood on the "unseen processes going on inside the customer's head" made him anxious, and often outraged. (more after the break)Waiters suffer such angst, he suggests, because no matter how hard they work, how wide they smile, how fast they dash, hardly any of it actually affects their tips. "Very often," he admits, "it's merely luck of the draw." That's true: Studies show that the tips a waiter receives only rarely reflect the quality of service provided. Yet Mr. Dublanica knew from experience that the reverse was not the case: "Good tippers get extra attention," he writes. "Bad tippers get seated near the toilets."

This funny and fascinating book looks at all the people in America who rely on tips—the cab driver, the garage attendant, the bartender, the doorman, just for starters—as the author wonders just what he'd have to tip to earn (or avoid) special treatment. He hits the road and gets acquainted with hairstylists, massage therapists, furniture deliverymen, phone-sex operators and dominatrixes. But though Mr. Dublanica presents "Keep the Change" as a "Quest to Become the Guru of the Gratuity," it's actually something more interesting: a study of how our professional and private lives are unavoidably intertwined.

Along the way we learn the details of all sorts of unusual trades. Bathroom attendants, for instance, are not only barely paid minimum wage but often must purchase with their own money the toiletries, treats and mouthwash they make available to customers. In Las Vegas, customers tip strippers to ensure repeat performances. But strippers in turn tip hosts (who allow them access to high-rollers) and, most important, also must tip the DJ's, who have the power to punish them by prolonging a lap dance with songs like "Free Bird." Then there are the hotel doormen. You tip them to flag a taxi, but they also receive kickbacks from buddies in the cab line who are looking for lucrative fares for jaunts to the airport. Some doormen in New York can earn between $80,000 to $100,000 a year, though they probably report an income half that to the IRS.

Mr. Dublanica admits that he, too, preferred to avoid taxes when possible and thus preferred cash tips. He heaps scorn on the practice of replacing tips with "service charges," at least at restaurants that aren't fine-dining establishments. He's not a big fan of pooling tips either. Ever notice that Starbucks tip jar—the one that doesn't actually say "tips" on it, since Starbucks forbids it? The proceeds are divided based on hours worked; so don't bother tipping that cute barista extra. "What is this?" Mr. Dublanica asks. "Caffeinated communism?" He prefers when an employee "eats what he kills."

Mainly the author seems fascinated by the ways that tipper and tippee manipulate and exploit each other. "Tipping is all about relationships," writes Mr. Dublanica, brief as they may be. The classic case is the bartender offering spirits and solace and hoping for more than a $1 tip. Says one barman: "You pay for your drink, see? And I have to break a twenty. Well, I'm going to put a five or a ten on top of the singles and hover over you." Mr. Dublanica suggests that the man is playing on guilt. He replies: "Guilt is the bartender's best friend."So what does make people tip the way they do—do they do it as a bribe, an expression of symp athy, a social obligation? All these motivations play a role, Mr. Dublanica concludes. We also often tip for fear of retribution—after reading this book, you'll be sure to generously tip your hotel housekeepers and parking valets. It may also be that we tip just to be liked. "This amazes people, but it's true," he insists. "When a waiter plays hard to get, that often increases a customer's desire to win his approval." Or perhaps people tip simply because it's the decent thing to do.

Eventually Mr. Dublanica gets around to offering advice on how to tip in various situations. Yet it's suspect, since he bases it on what workers in each field have said they wanted to receive. It turns out that when in doubt—whether it's for a stripper or a waiter—a 20% tip is just about right.

No comments:

Post a Comment